Science and Statistics: a brief review

All models are wrong; some are useful. But why is that? In this article, I review Box’s (1976) paper on the iterative process of scientific knowledge production.

In practically all disciplines across different fields of Science — Natural, Exact, or Social — one of the most fundamental discussions debated by scholars is the conceptualization of the discipline in question. In other words, it is a process of identification in order to apply. To conduct research in Statistics, one must know what Statistics is; to produce a historiographical work, one must know what History is, and so on. The task of defining a discipline, however, is not trivial, and more importantly: given a definition, it is certainly not unique, uncontested, or static. This is precisely why, over time, new methods of producing scientific knowledge are suggested and executed.

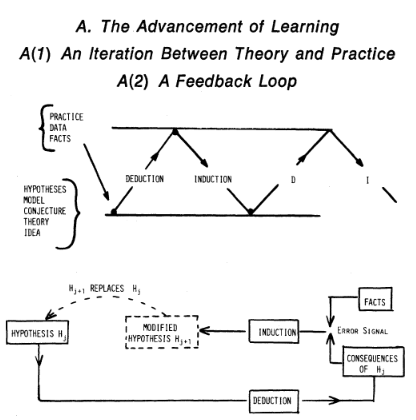

The article Science and Statistics (Box 1976) may, at first glance, seem like an uninteresting digression on how Ronald Fisher (1890-1962) contributed to the evolution of Statistics, in particular, and Science in general, through the methods he developed and improved. On the other hand, a more attentive reading reveals that Box (1976) actually presents his ideal view of how scientific knowledge should be produced1: “[…] not by mere theoretical speculation on one hand, nor by the undirected accumulation of practical facts on the other, but rather a motivated iteration between theory and practice […]” (Box 1976, 791).

Scientific practice, therefore, is understood by Box (1976) as a kind of loop, or a tentative theory. The researcher analyzes the available theory, makes deductions from it, and compares them to the facts — or data — that can be accessed. These two pieces of information, of distinct natures, do not necessarily converge, so the theory needs to be adjusted to explain a certain phenomenon. This new theory is compared to the facts again and so on, in a literally iterative process. The question is, therefore, the following: the confrontation between facts and theory produces errors, which imply the need to reassess one or the other element.

That is why “[…] all models are wrong […].” (Box 1976, 792). Naturally, all models are wrong because scientific practice results from a continuous comparison between theory and practice, so no matter how much a scientist elaborates their model in advance, it will likely need to be adapted when confronted with the factual. Box (1976), in this regard, refers to the fact that, in practice, there are no normal distributions or linearity in nature. That is, even though they are incorrect models (because they do not precisely correspond to what is found in nature), they are still useful for making approximations of what is found in the real world, as the result comes from the iteration between theory and practice. From a statistician’s point of view, the iterative process develops through a stage in which the scientist chooses the best statistical procedures to analyze the data and supports the model; in the next stage, after the analysis, they assume that the model contains errors and apply a series of residual analyses to improve it, and so on.

The examples based on a brief biography of Fisher serve, in practice, to illustrate the “best practices” of acquiring scientific knowledge. They focus on Fisher’s initial concern with solving some practical problem of scientific relevance and highlight Box (1976)’s ideal regarding scientific practice: one must not lose sight of the real problem to which certain statistical knowledge is being applied or even developed. Hence, the critiques of Mathematistry2, which is often disconnected from practical issues. It thus reinforces the importance of statisticians who can combine and confront theory and practice to, in fact, produce scientific knowledge.

References

Footnotes

In his argument, the author addresses Science in general. Ultimately, we must keep in mind that this proposition does not necessarily encompass all scientific disciplines. Nevertheless, we know that his concern is with the Exact Sciences in general, especially Statistics.↩︎

“Mathematistry is characterized by development of theory for theory’s sake which since it seldom touches down with practice, has a tendency to redefine the problem rather than solve it.” (Box 1976, 798).↩︎

Citation

@online{lamarca2024,

author = {Lamarca, Felipe},

title = {Science and {Statistics:} A Brief Review},

date = {2024-09-19},

langid = {en}

}